DISTRIBUTION OF ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE GENES IN THE ENVIRONMENT:

THE ROLE OF MINERAL FACILITATED HORIZONTAL GENE TRANSFER

Combining recent research across disciplines, I see evidence that minerals hold a high and unrecognized potential for enhancing the distribution of the ARg in the environment. Adsorption of ARg to minerals significantly increases the ARg’s lifetime and facilitates their distribution by sedimentary transport processes. In addition, minerals also serve as a) sites for horizontal gene transfer (HGT), b) platforms for microbial growth and, hence 3) act as hot spots for propagation of adsorbed ARg to other microbes. However, some minerals and ARg are bound more strongly than others and various bacteria have different affinities toward various minerals. Those variations in affinity are poorly quantified but vital for predicting the distribution of ARg in the environment.

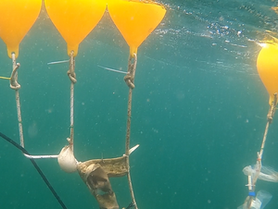

Bacterial colony formation.

Image by Lisselotte Jauffred (collaborator from NBI)

The spread of antibiotic resistance genes (ARg) is a worldwide health risk1 and is no longer only a clinical issue. Vast reservoirs of ARg are found in natural environments2–4 such as soils, sediments and oceans. The emergence and release of ARg to the environment is in particular caused by extended use of antibiotics in farming, e.g. where the genes dissipate from the manure.5 Once in the environment, the ARg are surprisingly rapidly propagated. It is well known that the ARg are distributed to neighbour bacteria through processes of both cell sharing or through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) where one species acquirer resistance from another.6,7 Most HGT responsible for the spread of ARg are assumed to be through direct microbe-microbe contact. However, I find that the outcome of non-contact transfer is grossly underestimated. In the HGT mechanism called “Transformation”, free ARg in suspension or adsorbed to a mineral can be picked up and incorporated into non-related organisms. Considering that free DNA only can survive for a few weeks in sea- and freshwater environments,8–10 any HGT from free DNA can rightly be assumed to be local, but if the DNA gets adsorbed to a mineral, it can survive for several hundred thousands of years.11–14 If this also holds for ARg, then minerals offer a potent mechanism for distributing ARg through our environments my means of sedimentary processes.

Karina K. Sand

Lektor / Associate professor

Bio-mineral interactions and their implications for life and health of humans, ecosystems and the environment

MOLECULAR GEOBIOLOGY GROUP

Bio-mineral interactions and their implications for life and health of humans, ecosystem,s and the environment

we apply in-situ molecular- to macro scale techniques to study bio-mineral interactions. Our overarching interests is to interrogate how bio-mineral interactions play a role for health aspects.

The interface between biology and mineralogy are vital for many aspects of life and health, . During my career I have focused on aspects such as the origin of life, the development of hard parts in organisms, how extracellular DNA stabilized on minerals, plastics or tissue can propagate antibiotic resistance genes or other traits, impact the evolution of life and how ecosystem health is linked to environmental stressors.

Currently we (group and collaborators) are focused on establishing fundamental information on how and why minerals can preserve DNA and proteins across time and space and how cells can utilize extracellular DNA that are adsorbed to substrates such as plastics, minerals and tissue.

For more implications and specific projects check below and the group page for more about us. I try to blog about ups and downs, but have to realize that it is mostly the positive stories that makes it there.

PROJECTS

Recent blog posts

Field work

Funding